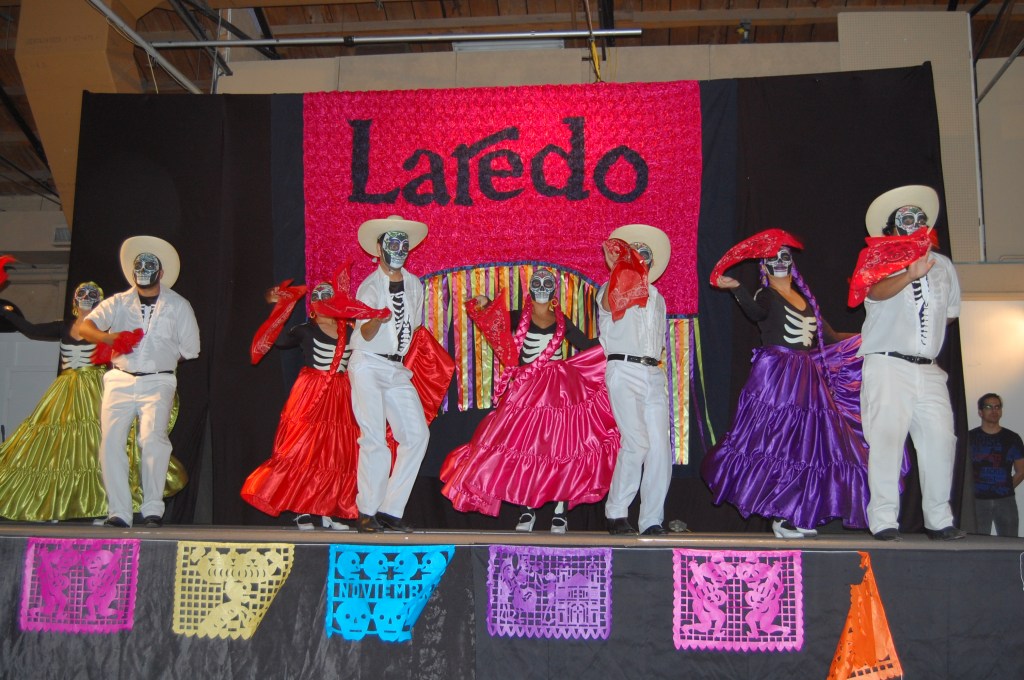

When I first started dancing folklorico as a college student at the University of Texas at Austin, my dance teacher, Michael Carmona, told us about Dia de los Muertos. I remember painting my face like a skeleton and dancing in our community in celebration of our ancestors. I have noticed that with the release of the Disney movie Coco, it seems like this event is even more popular than ever. Yet, I notice that when we dance as skeletons our movements take on additional meanings.

What is Dia de los Muertos?

Dia de los Muertos is translated as Day of the Dead in English. It is celebrated on November 1 and 2 in Mexico and all around the world. Mexicans believe that on these days the souls of the departed return to earth to visit their family and friends.

What is the history of Dia de los Muertos?

It is very difficult to pinpoint the origin of anything. However, scholars acknowledge that the customs surrounding Dia de los Muertos have an indigenous influence. For example, the Aztec people held special offerings and ceremonies to honor children and adults who had died. It was known asMiccailhuitontli and Miccailhuitl which is translated as Little Feast of the Dead and Great Feast of the Dead. This is just one example because Mexico is a very ethnically diverse country whereby indigenous andmestizo groups celebrated the death of their loved ones through song, dance, ritual, and offerings. In the sixteenth century with the Spanish conquest of Mexico, Catholic friars noticed that the indigenous people incorporated their own ceremonies celebrating the dead during the Catholic feast day of All Souls Day.

How do we celebrate Dia de los Muertos today?

Loved ones prepare for a visit by the deceased by creating an altar that is displayed in their home. The altar is decorated with all the favorite items of the departed including pictures. In addition, food is prepared and placed on the altar so that the loved one may return and partake. In my city of Laredo, Texas, many celebrate by visiting the cemetery and put flowers on the graves. Others attend a mass in memory of their loved ones. Many buy pan de muerto (bread of the dead) which is a type of sweat bread that has bone shapes and is sold at the local bakeries. Different villages, cities, and regions celebrate this custom in many different ways.

Who was José Guadalupe Posada?

José Guadalupe Posada (1851-1913) was an illustrator, print maker that worked for many different Mexican periodicals and presses. He is most known for his illustrations of calaveras (skulls) that were dressed in fancy clothing and infused with political satire. One of his most popular drawings was of a rich, female skeleton wearing a fancy hat with a feather on it. Posada dubbed this drawing La Calavera de la Catrina. Posada’s skeletal illustrations were not greatly appreciated until after his death. Since the 1920s and 1930s these skeletal images have been closely associated with celebrations of Dia de los Muertos.

How is Dia de los Muertos a Bodily Memory?

Folklorico dance groups celebrate Dia de los Muertos by dancing with their faces painted as skulls. Then, our dances take on additional meanings. Yes, we are still performing our Mexican cultural history when we dance. Yet, on Dia de los Muertos we are also performing as skeletons bringing to life the bodily memories of our ancestors. Oftentimes, when the dancers perform it may appear that the skeletal Catrina image depicted by Posada has come to life. I usually dedicate my own dancing to my beloved father, grandparents, aunt and my loved ones who are no longer physically on this earth. I remember them with every zapateado, grito, and skirt flourish. Sometimes I can feel their presence with me even stronger. This is the power of our dancing.

Works Cited

Berdecio, Roberto and Appelbaum, Stanley. Eds. Posada’s Popular Mexican Prints. Mineola: Dover Publications Inc., 1972. Print.

Carmichael, Elizabeth and Chloë Sayer. The Skeleton at the Feast: Day of the Dead in Mexico. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1991. Print.

Delsol, Christine. “La Catrina: Mexico’s Game of Death.” SF Gate. October. 2011. Web. 6 May. 2014.

Photos courtesy of Gabriela Mendoza-Garcia or are in the public domain.

Copyright, 10/28/2019, Mendoza-Garcia

Gabriela Mendoza-García Ph.D. is an Artist and Scholar. She has her own dance school and company called the Gabriela Mendoza-García Ballet Folklórico in Laredo, Texas. Dr. Mendoza-Garcia founded this group in 2013 and teaches children and adults of all ages. Her company consists of seasoned folklórico dancers with years of experience performing this art form. She teaches traditional Mexican folklórico dance pieces, as well as, works that are inspired by her scholarly research. Her scholarship includes: Dancing throughout Mexican History (1325-1910), History & Folklore booklet with an accompanying documentary sponsored by the Webb County Heritage Foundation, The Jarabe Tapatío: Imagining Race, Nation, Class and Gender in 1920s Mexico published by Oxford University Press, an on-line blog, writings for Asociación Nacional de Grupos Folklóricos, and others.