A few year back I met up with a friend of my during the Asociación Nacional de Grupos Folklóricos conference in Arizona. We talked about our families, and the challenges of teaching dance. At that time her son was two years old and mine was about five years. I told her that my son was taking folklórico classes with me. She told me that she was reluctant to enroll her son in folklórico. Surprised, I asked why. She responded, “what do you do with heteronormativity?” I have to admit, I was taken aback. But then, we had a wonderful conversation.

What is heteronormativity?

According to scholars Berlant and Warner, in Sex in Public (1998) they argue that heteronormativity is this underlined idea that male/female couples are the norm. This permeates our laws, customs, and even our dances (552-558). Yes, in our folklórico dances especially the bailes or social dances of Mexico we represent male/female couple relationships as the norm.

Dancing our Gender

Without even realizing it, many of the dances especially the social ones require men and women as dancing partners. In fact, men often dance with their legs wide apart, have their chest held out, and their torso bent forward to catch the woman in a kiss. Their long, blasting gritos and whistles fill the air as they dance. Women match the speed of the male yet they dance with their legs closer together, must move their arms and wrists in skirt work movements that complement the dance. Depending on the type of dance, women can be told to keep their gaze down to the floor with a shy expression while the man romantically pursues her. We perform specific gender role expectations as we dance. In fact, when we perform the bailes of Mexico we even reinforce heteronormativity—this expectation that men and women are a romantic couple. Very seldom is any other alternative given.

Campobello Sisters: Challenging Heteronormativity

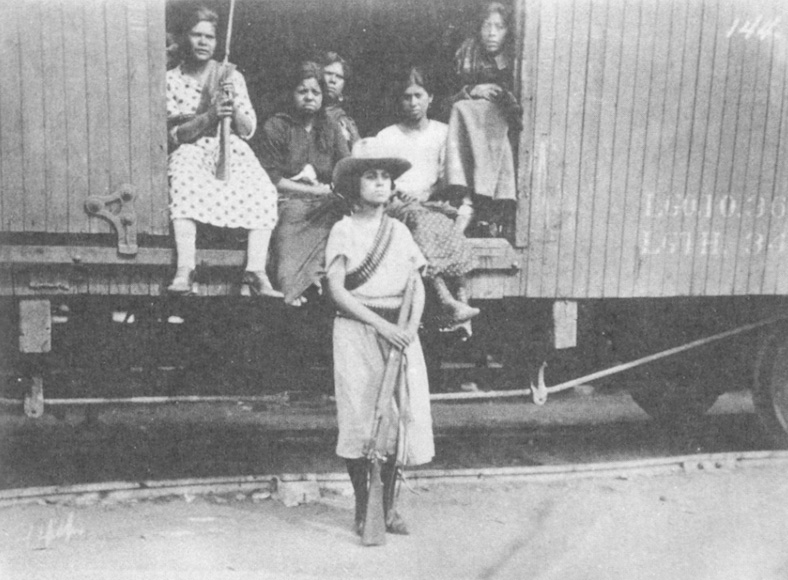

One famous sister duo to challenge heteronormativity was Nellie and Gloria Campobello. Nellie Campobello was born in 1900 while Gloria Campbello was born in 1911(Tapía 3,7, 9). In 1930, the sisters were employed as teachers in the National Music and Dance Section of the Department of Fine Arts of the Secretaría de Educación Pública (SEP) (Tortajada Quiroz 276).

According to Frances Toor in A Treasury of Mexican Folkways (1947) Nellie and Gloria Campobello premiered their own version of the Jarabe Tapatío as part of their work with the Department of Fine Arts of the SEP in 1930. Nellie performed the role of the Charro and Gloria performed the role of the China Poblana (Tortajada Quiroz 277). They danced together as a couple. I have to ask myself did Nellie take on the characteristics of the Charro and try to woo her sister Gloria when dancing? Was this female/female version of the Jarabe Tapatío well received?

I found a newspaper article written by Carlos del Rio in the 1930 about the sisters’ dance. Del Rio stated:

Nellie and Gloria Campobello discovered the true jarabe and they danced it without fear, passionately. The lack of a male dancer did not stop them. What helped Nellie was her experience with the outdoors, her taste of adventure, her silhouette as an admirable man who pursues, wins, and dominates the woman in a final joy (38). [i]

Well, it appears that Del Rio loved this interpretation of two women dancing the Jarabe Tapatío together. Del Rio was elated that the sisters did not need a male dancer for their duets. According to Del Rio, Nellie did take on the characteristics of the Charro she was described as adopting a behavior that was entirely masculine on stage because she pursued the woman, defeated her, dominated her and then ended the dance joyously.[ii]

There are many reasons why this dance might have been accepted. For example, the fact that they were sisters dancing together might have made it acceptable for them to perform this dance. In addition, it could be that the sisters might not have deliberately danced the Jarabe Tapatío to challenge heteronormativity but it could certainly have been read this way by those in the audience.

You can see a photograph of Nellie and Gloria Campobello dancing the Jarabe Tapatío together in 5:33 of this You Tube Video

Challenging Heteronormativity in the 21st Century

What do we do today to challenge heteronormativity? There are a few folklórico groups in the United States and Mexico that challenge heteronormativity. I spoke with Arturo Magaña of the Ensamble Folklórico Colibri whose purpose is “to create an artistic outlet for the LBGT community to express their heritage” (A. Magaña, pers. comm.). This dance group performs the dances of Mexico with its dancers choosing the gender roles. In this group sometimes their dancers perform with female/female partners, male/male partners or sometimes they dance with male/female partners.

More specifically, Magaña has challenged heteronormativity within his choreography. So for example, in his version of El Alcaraban from Chiapas. Instead of women/men couples courting each other, he choreographed a love dance between male/male couple. In his choreographic works, Magaña is not afraid to even go a step further. For example, instead of depicting the traditional Nayarit wedding with the female bride and male groom dancing at their wedding reception. Magaña choreographed a full cuadro of Nayarit depicting a lesbian wedding to tell the stories of the LBGT community. Magaña tells me that his work is accepted in embraced throughout California. To my surprise, he says that 99% of the negative reactions come from folkloristas (A. Magaña, pers. comm.).

My Thoughts

I can’t help but wonder why we (folkloristas) are the ones who are the most resistant to challenging heteronormativity. What are we holding onto? I think that as folkloristas we need to recognize the ways in which we reinforce heteronormativity in our teaching and our dances. It’s essential to point these instances out to our students, to ask questions, and most of all to have conversations and discussions. This is how we grow as folkloristas.

So, I go back to the original question. What do you do with heteronormativity?

Works Cited

Berlant, Lauren and Michael Warner. 1998. “Sex in Public.” Critical Inquiry 24 (2): 547-566.

Del Rio, Carlos. “Nelly y Gloria Campobello-Creadora de Danzas.” Revistas de Revistas: El Semanario Nacional.October 12. 1930.

Magaña, Arturo. 2019. Interview by author: December 13.

Tapía, Minverva. “Nellie Campobello: A Mexican Political Dance Pioneer.” MFA thesis. University of California at Irvine, 2006.

Toor, Frances. 1947. A Treasury of Mexican Folkways. New York: Crown Publishing.

Tortajada Quiroz, Margarita. 2001. Frutos de Mujer:Las Mujeres en la Danza Escenica. Mexico: Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura.

[i] This is my translation.

[ii] Later in life, Nellie Campobello served as Director of Mexico’s National School of Dance for forty-five years and directed the Mexico City Ballet. Gloria Campobello is remembered as having been Mexico’s first prima ballerina and taught at Mexico’s National School of dance (Tapia 24, 1, 11-13). The Campobello sisters would become celebrated as prominent dancers, educators, choreographers, researchers, and writers.

Photos courtesy of Gabriela Mendoza-Garcia. Video footage taken from You Tube.

Copyright, 12/12/2019, Mendoza-Garcia

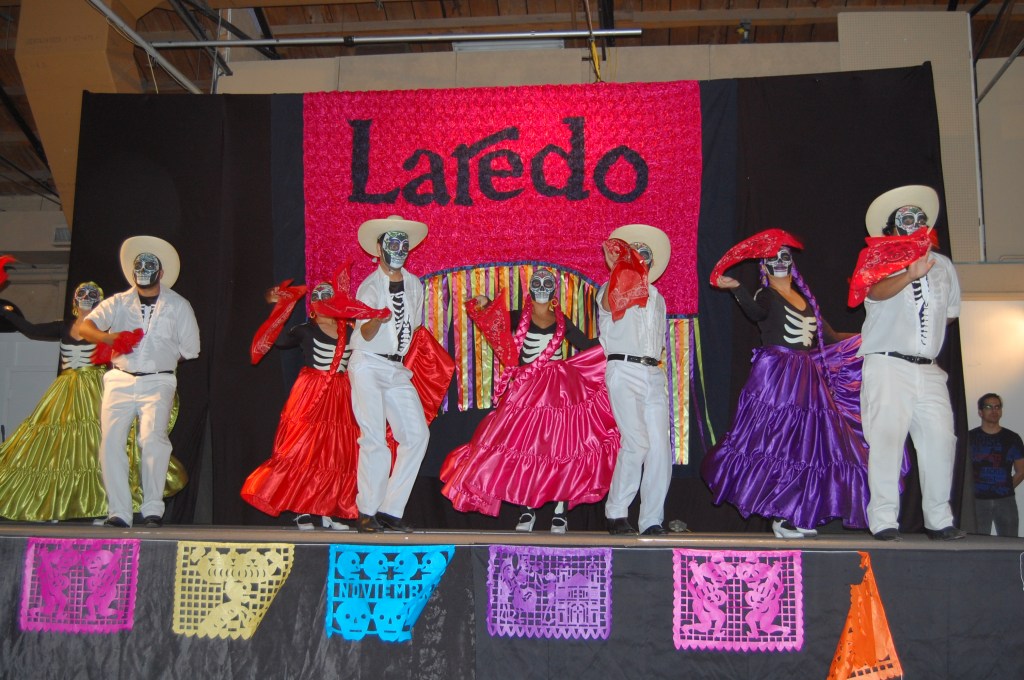

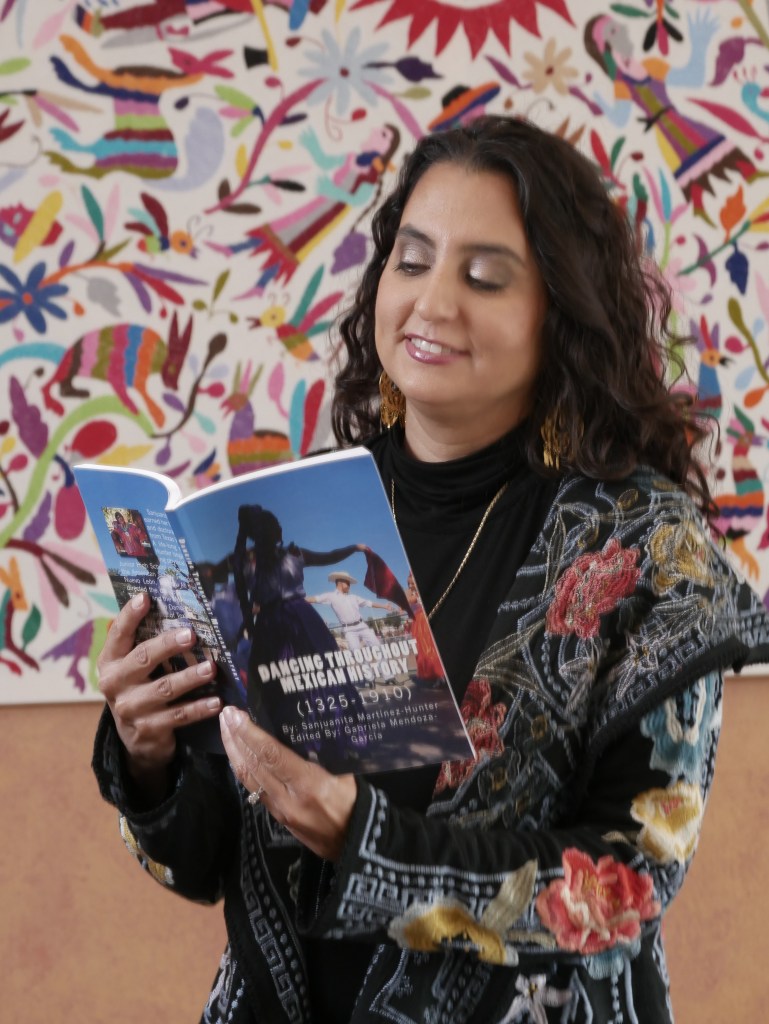

Gabriela Mendoza-García Ph.D. is an Artist and Scholar. She has her own dance school and company called the Gabriela Mendoza-García Ballet Folklórico in Laredo, Texas. Dr. Mendoza-Garcia founded this group in 2013 and teaches children and adults of all ages. Her company consists of seasoned folklórico dancers with years of experience performing this art form. She teaches traditional Mexican folklórico dance pieces, as well as, works that are inspired by her scholarly research. Her scholarship includes: Dancing throughout Mexican History (1325-1910), History & Folklore booklet with an accompanying documentary sponsored by the Webb County Heritage Foundation, The Jarabe Tapatío: Imagining Race, Nation, Class and Gender in 1920s Mexico published by Oxford University Press, an on-line blog, writings for Asociación Nacional de Grupos Folklóricos, and others.