I could never have imagined the position that we are in–never in my wildest dreams. It began with me seeing all the postings on Facebook of my colleagues in California cancelling their concerts, classes, and even events. I noticed my friends in other states began to do the same. In Texas, Governor Abbot declared that all public schools would be closed until April 3rd. That is when it hit home! I suspended all my dance classes. I began to share warm-up exercises, zapateado techniques, and even host a few Facebook live on-line classes just so that we wouldn’t completely stop dancing folklórico entirely. I had to re-think this entire situation. And these are my thoughts.

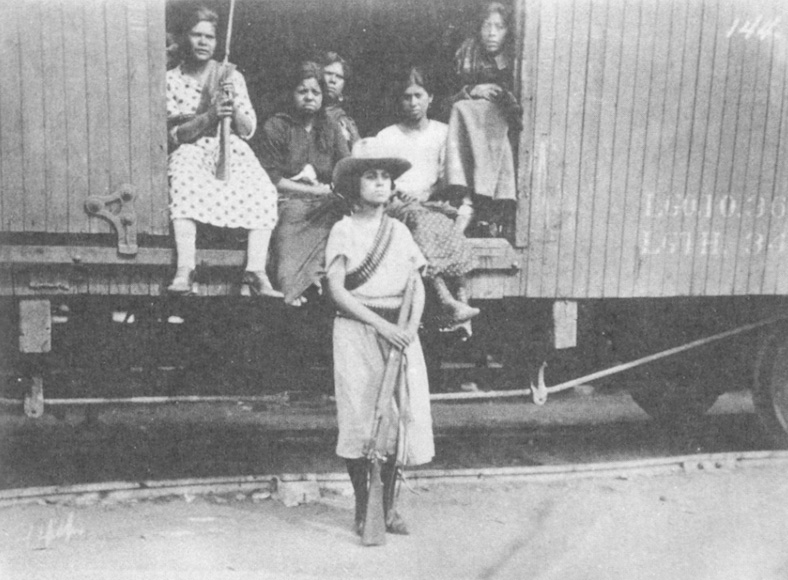

We come from a very strong people. Our people have overcome conquest, colonization, and even genocide. We adapted and survived the European colonization of the Americas, the Spanish inquisition, the War of Independence from Spain, the Reform Wars, the Mexican-American War, the Mexican Revolution, etc. In the United States, our people are both native people and immigrants to this country. We struggled and fought in many wars such as the American Revolution, American Indian Wars, the Mexican-American War, the Civil War, World War I, World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the Iraq War, the Gulf War, etc. We protested and fought for our civil rights during the Chicano Movement. We continue this fight even today. Our music and dance traditions continuously transform. They are inspired by the political events around us. We did not stop dancing in times of hardship. During the Spanish Inquisition, our people were punished with three hundred lashes with a whip, fined, and put in jail for singing and dancing the jarabes. This did not stop us from playing our music, singing our songs, and dancing.

Our people survived small pox which killed millions of indigenous people throughout the Americas in the 1500s. In Tenochtitlán approximately 150,000 died of small pox. We are the survivors of the measles, syphilis, influenza, etc. Throughout this decimation our ancestors continued dancing. Perhaps the reason we express so much joy in our dances is because our people turned to music and dance as a survival mechanism. Think about it, for a few hours they could leave their problems behind them while they danced. We should do the same

So, we shall too overcome this pandemic. As Folkloristas we are the storytellers, the shamans, the bearers of our cultural dance traditions in the twenty-first century. We will adapt, change, and continue dancing just as our ancestors before us. We will persevere!

Cover photo courtesy of Gabriela Mendoza-Garcia. Photos are in the public domain.

Copyright, 3/29/2020, Mendoza-Garcia

Gabriela Mendoza-García Ph.D. is an Artist and Scholar. She has her own dance school and company called the Gabriela Mendoza-García Ballet Folklórico in Laredo, Texas. Dr. Mendoza-Garcia founded this group in 2013 and teaches children and adults of all ages. Her company consists of seasoned folklórico dancers with years of experience performing this art form. She teaches traditional Mexican folklórico dance pieces, as well as, works that are inspired by her scholarly research. Her scholarship includes: Dancing throughout Mexican History (1325-1910), History & Folklore booklet with an accompanying documentary sponsored by the Webb County Heritage Foundation, The Jarabe Tapatío: Imagining Race, Nation, Class and Gender in 1920s Mexico published by Oxford University Press, an on-line blog, writings for Asociación Nacional de Grupos Folklóricos, and others.